MSU Researchers to Study Avian Flu in Dairy Cattle, Prevention

May 15, 2024

Nik Rajkovic / news@whmi.com

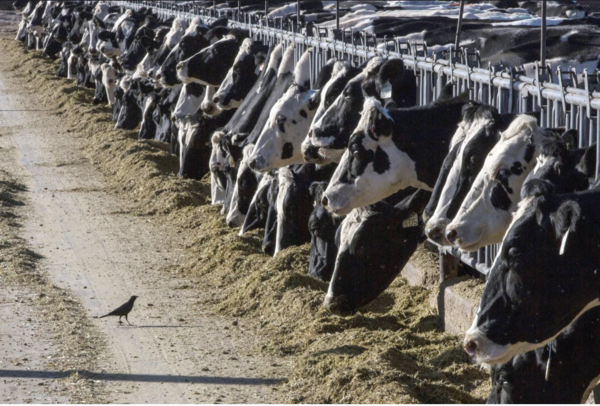

New research from Michigan State University will study the effects of a recent highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus (H5N1) outbreak on dairy cattle reproduction and milk production, as well as transmission of the disease and ways to mitigate it.

Support for the new project has been provided through two sources, each covering half of the $168,000 total:

• Annual capacity funding through MSU AgBioResearch from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

• Capacity funding through the Michigan Alliance for Animal Agriculture, a partnership among MSU, Michigan animal agriculture industries and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD).

The project is co-led by Catalina Picasso, Zelmar Rodriguez and Annette O’Connor, faculty members in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences (LCS). Picasso is a veterinarian and epidemiologist, specializing in transboundary infectious diseases in both livestock and wildlife animal populations. Rodriguez is a dairy health epidemiologist and dairy extension faculty member.

O’Connor is a world-renowned veterinarian and expert in the application of quantitative epidemiology to improve policy on food safety, animal health and welfare, and veterinary practices.

According to the USDA, as of mid-May, H5N1 infections have been detected in dozens of dairy herds across Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, and Texas.

The virus, which was first detected in domestic birds in the U.S. in 2022 but not until recently in cattle, has been identified in unpasteurized milk, as well as swabs and tissue samples from sick cattle.

Symptoms may include reduced milk production, decreased appetite, and changes in milk color and consistency.

“Immediately upon the onset of the H5N1 outbreak in Michigan dairy cattle, MSU AgBioResearch, the College of Veterinary Medicine and MDARD began conversations about research questions that when answered could inform policy and management strategies to help prevent transmission within and across dairy herds,” said James Averill, assistant director of MSU AgBioResearch and leader of the organization’s animal agriculture initiatives.

“This research will enable the dairy industry to better understand H5N1 and the impacts on dairy herds over time.”

The research team will seek to answer several key questions, such as:

• Impact: What are the short- and long-term effects of the disease on reproduction and milk production?

• At the herd level: What factors influence the likelihood of herds becoming infected?

• At the cow level: What increases or decreases the likelihood of cows becoming infected?

• Transmission: How is the virus spreading within and between herds?

“There’s still an enormous amount of information we don’t know,” O’Connor said.

“This outbreak underscored the critical need to understand the dynamics, impact and prevention of H5N1 among the cattle population. We are fortunate to be able to ground this research in on-farm studies, working closely with MDARD to access farms that have had herds test positive for the virus.”

The team plans to conduct five studies on farms with H5N1-positive animals. They will study lactating cows, dry cows and calves, collecting blood, nasal swabs and milk samples to be tested. All H5N1 testing is being performed by the MSU Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, the only laboratory in Michigan approved by the USDA to test for highly pathogenic avian influenza in any species.

Additionally, researchers will examine milking equipment for H5N1 presence and compare testing accuracy between pooled and individual samples.

Data from Michigan farms will be combined with findings from other universities nationwide for a comprehensive analysis.

“We’re trying to understand how long animals are shedding the virus and how long the virus stays active,” O’Connor said.

“For example, if we were to find that cattle are often positive on nasal swabs, we might conclude that nose-to-nose contact is a common route of transmission. Likewise, we may see that some samples come back negative quite often and show that those routes are much less likely. The overall goal is to equip our producers with the information needed to make informed decisions on how to best protect their cattle, and by extension, animal safety more broadly.”